What Was the Iconoclastic Controversy and How Did It Affect Secular and Religious Art?

The Byzantine Iconoclasm (Greek: Εικονομαχία, romanized: Eikonomachía , lit.'prototype struggle', 'state of war on icons') were two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the apply of religious images or icons was opposed past religious and imperial authorities within the Orthodox Church and the temporal imperial hierarchy. The Start Iconoclasm, as it is sometimes called, occurred betwixt about 726 and 787, while the Second Iconoclasm occurred betwixt 814 and 842.[1] Co-ordinate to the traditional view, Byzantine Iconoclasm was started past a ban on religious images promulgated by the Byzantine Emperor Leo Three the Isaurian, and continued nether his successors.[2] It was accompanied by widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of supporters of the veneration of images. The Papacy remained firmly in support of the use of religious images throughout the menstruation, and the whole episode widened the growing divergence between the Byzantine and Carolingian traditions in what was still a unified European Church, as well every bit facilitating the reduction or removal of Byzantine political control over parts of the Italian Peninsula.

Iconoclasm is the deliberate destruction within a culture of the civilization'southward own religious images and other symbols or monuments, usually for religious or political motives. People who appoint in or support iconoclasm are called iconoclasts, Greek for "breakers of icons" ( εἰκονοκλάσται ), a term that has come to be practical figuratively to any person who breaks or disdains established dogmata or conventions. Conversely, people who revere or venerate religious images are derisively called "iconolaters" ( εἰκονολάτρες ). They are commonly known as "iconodules" ( εἰκονόδουλοι ), or "iconophiles" ( εἰκονόφιλοι ). These terms were, nonetheless, non a part of the Byzantine fence over images. They take been brought into common usage past mod historians (from the seventeenth century) and their application to Byzantium increased considerably in the late twentieth century. The Byzantine term for the debate over religious imagery, "iconomachy," ways "struggle over images" or "image struggle". Some sources also say that the Iconoclasts were against intercession to the saints and denied the usage of relics, however it is disputed.[1]

Iconoclasm has generally been motivated theologically by an Onetime Covenant interpretation of the Ten Commandments, which forbade the making and worshipping of "graven images" (Exodus twenty:4, Deuteronomy five:eight, meet also Biblical police in Christianity). The ii periods of iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire during the eighth and ninth centuries made use of this theological theme in discussions over the propriety of images of holy figures, including Christ, the Virgin (or Theotokos) and saints. It was a debate triggered by changes in Orthodox worship, which were themselves generated by the major social and political upheavals of the 7th century for the Byzantine Empire.

Traditional explanations for Byzantine iconoclasm take sometimes focused on the importance of Islamic prohibitions against images influencing Byzantine thought. According to Arnold J. Toynbee,[3] for example, it was the prestige of Islamic military machine successes in the seventh and 8th centuries that motivated Byzantine Christians to adopt the Islamic position of rejecting and destroying devotional and liturgical images. The function of women and monks in supporting the veneration of images has also been asserted. Social and form-based arguments have been put forward, such equally that iconoclasm created political and economic divisions in Byzantine society; that it was generally supported by the Eastern, poorer, not-Greek peoples of the Empire[four] who had to constantly deal with Arab raids. On the other mitt, the wealthier Greeks of Constantinople and as well the peoples of the Balkan and Italian provinces strongly opposed Iconoclasm.[4] Re-evaluation of the written and material evidence relating to the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm by scholars including John Haldon and Leslie Brubaker has challenged many of the basic assumptions and factual assertions of the traditional account. Byzantine iconoclasm influenced the after Protestant reformation.[5] [6]

Background [edit]

Christian worship by the sixth century had developed a clear conventionalities in the intercession of saints. This belief was likewise influenced past a concept of hierarchy of sanctity, with the Trinity at its height, followed by the Virgin Mary, referred to in Greek equally the Theotokos ("birth-giver of God") or Meter Theou ("Mother of God"), the saints, living holy men, women, and spiritual elders, followed by the residuum of humanity. Thus, in club to obtain blessings or divine favour, early on Christians, like Christians today, would often pray or ask an intermediary, such equally the saints or the Theotokos, or living young man Christians believed to exist holy, to intercede on their behalf with Christ. A strong sacramentality and conventionalities in the importance of physical presence too joined the belief in intercession of saints with the use of relics and holy images (or icons) in early Christian practices.[8]

Believers would, therefore, make pilgrimages to places sanctified past the physical presence of Christ or prominent saints and martyrs, such as the site of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Relics, or holy objects (rather than places), which were a part of the claimed remains of, or had supposedly come into contact with, Christ, the Virgin or a saint, were also widely utilized in Christian practices at this time. Relics, a firmly embedded part of veneration by this period, provided physical presence of the divine but were non infinitely reproducible (an original relic was required), and still usually required believers to undertake pilgrimage or have contact with somebody who had.

The apply of images had greatly increased during this catamenia, and had generated a growing opposition among many in the church, although the progress and extent of these views is at present unclear. Images in the form of mosaics and paintings were widely used in churches, homes and other places such equally over city gates, and had since the reign of Justinian I been increasingly taking on a spiritual significance of their ain, and regarded at least in the popular mind every bit capable of possessing capacities in their own right, so that "the image acts or behaves as the subject area itself is expected to act or bear. It makes known its wishes ... It enacts evangelical teachings, ... When attacked information technology bleeds, ... [and] In some cases it defends itself confronting infidels with physical force ...".[9] Key artefacts to mistiness this boundary emerged in c. 570 in the course of miraculously created acheiropoieta or "images not made by man hands". These sacred images were a class of contact relic, which additionally were taken to bear witness divine approval of the apply of icons. The two most famous were the Mandylion of Edessa (where information technology still remained) and the Image of Camuliana from Cappadocia, past then in Constantinople. The latter was already regarded as a palladium that had won battles and saved Constantinople from the Persian-Avar siege of 626, when the Patriarch paraded it around the walls of the city. Both were images of Christ, and at to the lowest degree in some versions of their stories supposedly made when Christ pressed a cloth to his face (compare with the afterwards, western Veil of Veronica and Turin shroud). In other versions of the Mandylion'due south story information technology joined a number of other images that were believed to take been painted from the life in the New Testament period by Saint Luke or other human painters, again demonstrating the support of Christ and the Virgin for icons, and the continuity of their employ in Christianity since its start. G. East. von Grunebaum has said "The iconoclasm of the eighth and ninth centuries must exist viewed as the climax of a movement that had its roots in the spirituality of the Christian concept of the divinity."[10]

The events of the seventh century, which was a menses of major crisis for the Byzantine Empire, formed a catalyst for the expansion of the employ of images of the holy and caused a dramatic shift in responses to them. Whether the acheiropoieta were a symptom or cause, the tardily 6th to eighth centuries witnessed the increasing thinning of the boundary between images not made past human easily, and images made past human hands. Images of Christ, the Theotokos and saints increasingly came to exist regarded, as relics, contact relics and acheiropoieta already were, equally points of access to the divine. By praying before an image of a holy effigy, the believer'southward prayers were magnified by proximity to the holy. This modify in exercise seems to have been a major and organic development in Christian worship, which responded to the needs of believers to have admission to divine support during the insecurities of the seventh century. It was non a change orchestrated or controlled by the Church building. Although the Quinisext quango did non explicitly state that images should be prayed to, it was a legitimate source of Church building authority that stated images of Christ were acceptable as a consequence of his human incarnation. Considering Jesus manifested himself equally homo it was acceptable to make images of him but like it was adequate to make images of the saints and other humans.[11] The events which have traditionally been labelled 'Byzantine Iconoclasm' may be seen as the efforts of the organised Church and the imperial authorities to answer to these changes and to try to reassert some institutional control over pop practice.

The rise of Islam in the seventh century had likewise caused some consideration of the use of holy images. Early Islamic belief stressed the venial of iconic representation. Earlier scholarship tried to link Byzantine Iconoclasm directly to Islam by arguing that Byzantine emperors saw the success of the early on Caliphate and decided that Byzantine use of images (as opposed to Islamic aniconism) had angered God. This does not seem entirely plausible notwithstanding. The utilise of images had probably been increasing in the years leading up to the outbreak of iconoclasm.[12] I notable change came in 695, when Justinian 2 put a total-faced image of Christ on the obverse of his gold coins. The effect on iconoclast opinion is unknown, but the change certainly acquired Caliph Abd al-Malik to break permanently with his previous adoption of Byzantine coin types to start a purely Islamic coinage with lettering just.[thirteen] This appears more like two opposed camps asserting their positions (pro and anti images) than one empire seeking to imitate the other. More than striking is the fact that Islamic iconoclasm rejected any depictions of living people or animals, not only religious images. By dissimilarity, Byzantine iconomachy concerned itself only with the question of the holy presence (or lack thereof) of images. Thus, although the rise of Islam may take created an environs in which images were at the forefront of intellectual question and argue, Islamic iconoclasm does not seem to have had a straight causal part in the evolution of the Byzantine epitome debate; in fact Muslim territories became havens for iconophile refugees.[xiv] However, it has been argued that Leo III, because of his Syrian background, could have been influenced by Islamic beliefs and practises, which could accept inspired his first removal of images.[15]

The goal of the iconoclasts was[16] to restore the church to the strict opposition to images in worship that they believed characterized at the to the lowest degree some parts of the early church. Theologically, i aspect of the debate, as with most in Christian theology at the time, revolved effectually the two natures of Jesus. Iconoclasts believed[14] that icons could not correspond both the divine and the human natures of the Messiah at the same time, but simply separately. Considering an icon which depicted Jesus every bit purely physical would be Nestorianism, and one which showed Him as both human and divine would non be able to practise so without confusing the ii natures into ane mixed nature, which was Monophysitism, all icons were thus heretical.[17] Leo 3 did preach a series of sermons in which he drew attention to the excessive behaviour of the iconodules, which Leo 3 stated was in direct opposition to Mosaic Law as shown in the Second Commandment.[xviii] However, no detailed writings setting out iconoclast arguments take survived; nosotros have only cursory quotations and references in the writings of the iconodules and the nature of Biblical constabulary in Christianity has always been in dispute.

Sources [edit]

A thorough agreement of the Iconoclast flow in Byzantium is complicated by the fact that most of the surviving sources were written by the ultimate victors in the controversy, the iconodules. It is thus hard to obtain a complete, objective, balanced, and reliably authentic account of events and diverse aspects of the controversy.[19] The catamenia was marked past intensely polarized fence amongst at least the clergy, and both sides came to regard the position of the other as heresy, and appropriately fabricated efforts to destroy the writings of the other side when they had the adventure. Leo 3 is said to have ordered the destruction of iconodule texts at the start of the controversy, and the records of the concluding 2d Quango of Nicaea record that books with missing pages were reported and produced to the council.[xx] Many texts, including works of hagiography and historical writing besides as sermons and theological writings, were undoubtedly "improved", made or backdated past partisans, and the hard and highly technical scholarly process of attempting to assess the real authors and dates of many surviving texts remains ongoing. Most iconoclastic texts are only missing, including a proper record of the council of 754, and the detail of iconoclastic arguments take more often than not to be reconstructed with difficulty from their vehement rebuttals past iconodules.

Major historical sources for the period include the chronicles of Theophanes the Confessor[21] and the Patriarch Nikephoros,[22] both of whom were agog iconodules. Many historians have also drawn on hagiography, well-nigh notably the Life of St. Stephen the Younger,[23] which includes a detailed, but highly biased, account of persecutions during the reign of Constantine Five. No account of the menses in question written by an iconoclast has been preserved, although certain saints' lives do seem to preserve elements of the iconoclast worldview.[24]

Major theological sources include the writings of John of Damascus,[25] Theodore the Studite,[26] and the Patriarch Nikephoros, all of them iconodules. The theological arguments of the iconoclasts survive but in the class of selective quotations embedded in iconodule documents, most notably the Acts of the Second Council of Nicaea and the Antirrhetics of Nikephoros.[27]

The first iconoclast period: 730–787 [edit]

![]()

An firsthand precursor of the controversy seems to accept been a large submarine volcanic eruption in the summertime of 726 in the Aegean Sea between the isle of Thera (modern Santorini) and Therasia, probably causing tsunamis and peachy loss of life. Many, probably including Leo III,[28] interpreted this as a judgment on the Empire by God, and decided that utilize of images had been the offense.[29] [30]

The classic account of the commencement of Byzantine Iconoclasm relates that sometime between 726 and 730 the Byzantine Emperor Leo 3 the Isaurian ordered the removal of an image of Christ, prominently placed over the Chalke Gate, the ceremonial entrance to the Bully Palace of Constantinople, and its replacement with a cross. Fearing that they intended sacrilege, some of those who were assigned to the task were murdered by a band of iconodules. Accounts of this event (written significantly later) suggest that at least role of the reason for the removal may have been military reversals against the Muslims and the eruption of the volcanic island of Thera,[31] which Leo possibly viewed as testify of the Wrath of God brought on past image veneration in the Church.[32]

Leo is said to have described mere epitome veneration as "a craft of idolatry." He apparently forbade the veneration of religious images in a 730 edict, which did not apply to other forms of art, including the image of the emperor, or religious symbols such as the cross. "He saw no need to consult the Church, and he appears to take been surprised by the depth of the popular opposition he encountered".[33] Germanos I of Constantinople, the iconophile Patriarch of Constantinople, either resigned or was deposed following the ban. Surviving letters Germanos wrote at the fourth dimension say little of theology. According to Patricia Karlin-Hayter, what worried Germanos was that the ban of icons would show that the Church had been in fault for a long fourth dimension and therefore play into the hands of Jews and Muslims.[34]

This interpretation is at present in doubt, and the debate and struggle may have initially begun in the provinces rather than in the imperial courtroom. Letters survive written by the Patriarch Germanos in the 720s and 730s concerning Constantine, the bishop of Nakoleia, and Thomas of Klaudioupolis. In both sets of letters (the earlier ones concerning Constantine, the later ones Thomas), Germanos reiterates a pro-image position while lamenting the behavior of his subordinates in the church, who evidently had both expressed reservations most image worship. Germanos complains "now whole towns and multitudes of people are in considerable agitation over this matter".[35] In both cases, efforts to persuade these men of the propriety of image veneration had failed and some steps had been taken to remove images from their churches. Significantly, in these messages, Germanos does not threaten his subordinates if they neglect to change their beliefs. He does non seem to refer to a factional split in the church, simply rather to an ongoing issue of concern, and Germanos refers to Emperor Leo III, often presented equally the original Iconoclast, as a friend of images. Germanos' concerns are mainly that the actions of Constantine and Thomas should non confuse the laity.

At this stage in the argue, there is no clear bear witness for an imperial involvement in the debate, except that Germanos says he believes that Leo III supports images, leaving a question as to why Leo III has been presented every bit the arch-iconoclast of Byzantine history. Almost all of the evidence for the reign of Leo III is derived from textual sources, the majority of which post-date his reign considerably, almost notably the Life past Stephen the Younger and the Relate of Theophanes the Confessor. These important sources are fiercely iconophile and are hostile to the Emperor Constantine 5 (741–775). Equally Constantine's begetter, Leo likewise became a target. Leo'south bodily views on icon veneration remain obscure, simply in whatsoever case, may not have influenced the initial phase of the debate.

During this initial period, concern on both sides seems to accept had piffling to do with theology and more with practical show and effects. In that location was initially no church building quango, and no prominent patriarchs or bishops called for the removal or devastation of icons. In the process of destroying or obscuring images, Leo is said to take "confiscated valuable church plate, altar cloths, and reliquaries decorated with religious figures",[33] merely he took no astringent action against the former patriarch or iconophile bishops.

In the Westward, Pope Gregory III held two synods at Rome and condemned Leo'south actions, and in response, Leo confiscated papal estates in Calabria and Sicily, detaching them too every bit Illyricum from Papal governance and placing them under the governance of the Patriarch of Constantinople.[36]

Ecumenical councils [edit]

14th-century miniature of the destruction of a church under the orders of the iconoclast emperor Constantine V Copronymus

Leo died in 741, and his son and heir, Constantine 5 (741–775), was personally committed to an anti-image position. Despite his successes as an emperor, both militarily and culturally, this has caused Constantine to be remembered unfavorably by a body of source material that is preoccupied with his opposition to paradigm veneration. For example, Constantine is defendant of being obsessive in his hostility to images and monks; considering of this he burned monasteries and images and turned churches into stables, co-ordinate to the surviving iconophile sources.[37] In 754 Constantine summoned the Council of Hieria in which some 330 to 340 bishops participated and which was the first church building council to business organisation itself primarily with religious imagery. Constantine seems to have been closely involved with the council, and information technology endorsed an iconoclast position, with 338 assembled bishops declaring, "the unlawful art of painting living creatures blasphemed the fundamental doctrine of our salvation--namely, the Incarnation of Christ, and contradicted the six holy synods. ... If anyone shall endeavour to correspond the forms of the Saints in lifeless pictures with material colors which are of no value (for this notion is vain and introduced by the devil), and does not rather stand for their virtues as living images in himself, etc. ... let him be anathema." This Council claimed to exist the legitimate "7th Ecumenical Council",[38] but its legitimacy is disregarded past both Orthodox and Catholic traditions as no patriarchs or representatives of the five patriarchs were present: Constantinople was vacant while Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria were controlled by Muslims, and Rome did not send a representative.

![]()

The iconoclast Council of Hieria was not the end of the matter, withal. In this menstruation complex theological arguments appeared, both for and against the use of icons. Constantine himself wrote opposing the veneration of images, while John of Damascus, a Syrian monk living exterior of Byzantine territory, became a major opponent of iconoclasm through his theological writings.[39]

It has been suggested that monasteries became hush-hush bastions of icon support, only this view is controversial. A possible reason for this interpretation is the desire in some historiography on Byzantine Iconoclasm to run across it as a preface to the later Protestant Reformation in western Europe, in which monastic establishments suffered harm and persecution.[ citation needed ] In opposition to this view, others have suggested that while some monks continued to support paradigm veneration, many others followed church and imperial policy.[ citation needed ]

The surviving sources accuse Constantine V of moving confronting monasteries, having relics thrown into the sea, and stopping the invocation of saints. Monks were forced to parade in the Hippodrome, each hand-in-hand with a adult female, in violation of their vows. In 765 St Stephen the Younger was killed, and was later considered a martyr to the Iconophile cause. A number of large monasteries in Constantinople were secularised, and many monks fled to areas across effective imperial control on the fringes of the Empire.[39]

Constantine's son, Leo 4 (775–80), was less rigorous, and for a time tried to mediate betwixt the factions. When he died, his wife Irene took power as regent for her son, Constantine 6 (780–97). Though icon veneration does not seem to have been a major priority for the regency government, Irene called an ecumenical council a year afterward Leo's decease, which restored image veneration. This may accept been an effort to secure closer and more than cordial relations betwixt Constantinople and Rome.

Irene initiated a new ecumenical council, ultimately called the Second Quango of Nicaea, which showtime met in Constantinople in 786 but was disrupted past war machine units faithful to the iconoclast legacy. The council convened again at Nicaea in 787 and reversed the decrees of the previous iconoclast council held at Constantinople and Hieria, and appropriated its title as 7th Ecumenical Quango. Thus there were 2 councils called the "Seventh Ecumenical Council," the outset supporting iconoclasm, the 2nd supporting icon veneration.

Unlike the iconoclast council, the iconophile council included papal representatives, and its decrees were approved past the papacy. The Orthodox Church considers it to exist the concluding genuine ecumenical quango. Icon veneration lasted through the reign of Empress Irene's successor, Nikephoros I (reigned 802–811), and the two cursory reigns after his.

Decree of the Second council of Nicaea [edit]

On October 13, 787 the 2nd Council of Nicaea decreed that 'venerable and holy images are to be dedicated in the holy churches of God, namely the prototype of our Lord and God and Saviour Jesus Christ, of our immaculate Lady the Holy Theotokos, and of the angels and all the saints. They are to be accorded the veneration of award, not indeed the true worship paid to the divine nature alone, but in the same way, as this is accorded to the life-giving cross, the holy gospels, and other sacred offerings' (trans. Toll, The Acts of the Second Quango of Nicaea [Liverpool 2018], 564-5, abbreviated).

The 2nd iconoclast menstruation: 814–843 [edit]

Emperor Leo V the Armenian instituted a second period of Iconoclasm in 815, over again possibly motivated by war machine failures seen as indicators of divine displeasure, and a want to replicate the military success of Constantine V. The Byzantines had suffered a series of humiliating defeats at the hands of the Bulgarian Khan Krum, in the course of which emperor Nikephoros I had been killed in battle and emperor Michael I Rangabe had been forced to abdicate.[twoscore] In June 813, a month before the coronation of Leo 5, a group of soldiers broke into the imperial mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles, opened the sarcophagus of Constantine 5, and implored him to return and salvage the empire.[41]

Soon after his accession, Leo V began to talk over the possibility of reviving iconoclasm with a diversity of people, including priests, monks, and members of the senate. He is reported to take remarked to a group of advisors that:

all the emperors, who took upwards images and venerated them, met their expiry either in revolt or in war; just those who did not venerate images all died a natural death, remained in ability until they died, and were then laid to rest with all honors in the purple mausoleum in the Church of the Holy Apostles.[42]

Leo next appointed a "commission" of monks "to look into the sometime books" and reach a decision on the veneration of images. They soon discovered the acts of the Iconoclastic Synod of 754.[43] A first contend followed between Leo's supporters and the clerics who connected to abet the veneration of icons, the latter group existence led by the Patriarch Nikephoros, which led to no resolution. Yet, Leo had apparently become convinced by this signal of the correctness of the iconoclast position, and had the icon of the Chalke gate, which Leo Three is fictitiously claimed to have removed once before, replaced with a cross.[44] In 815 the revival of iconoclasm was rendered official by a Synod held in the Hagia Sophia.

Leo was succeeded past Michael Ii, who in an 824 letter to the Carolingian emperor Louis the Pious lamented the advent of image veneration in the church and such practices as making icons baptismal godfathers to infants. He confirmed the decrees of the Iconoclast Council of 754.

Michael was succeeded by his son, Theophilus. Theophilus died leaving his married woman Theodora regent for his minor heir, Michael Iii. Like Irene fifty years earlier her, Theodora presided over the restoration of icon veneration in 843, on the condition that Theophilus non be condemned. Since that time the beginning Sunday of Nifty Lent has been celebrated in the Orthodox Church building and in Byzantine Rite Catholicism as the feast of the "Triumph of Orthodoxy".

Arguments in the struggle over icons [edit]

Iconoclast arguments [edit]

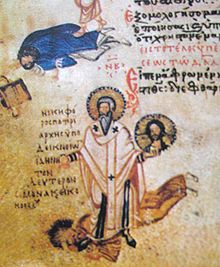

This page of the Iconodule Chludov Psalter, illustrates the line "They gave me gall to eat; and when I was thirsty they gave me vinegar to drinkable" with a flick of a soldier offering Christ vinegar on a sponge attached to a pole. Below is a movie of the last Iconoclast Patriarch of Constantinople, John VII rubbing out a painting of Christ with a similar sponge attached to a pole. John is caricatured, hither as on other pages, with untidy straight hair sticking out in all directions, which was meant to portray him as wild and barbaric.

What accounts of iconoclast arguments remain are largely constitute in quotations or summaries in iconodule writings. It is thus difficult to reconstruct a balanced view of the popularity or prevalence of iconoclast writings. The major theological arguments, however, remain in evidence because of the demand in iconophile writings to tape the positions existence refuted. Debate seems to have centred on the validity of the depiction of Jesus, and the validity of images of other figures followed on from this for both sides. The main points of the iconoclast argument were:

- Iconoclasm condemned the making of whatever lifeless prototype (e.m. painting or statue) that was intended to represent Jesus or i of the saints. The Image of the Definition of the Iconoclastic Conciliabulum held in 754 declared:

"Supported by the Holy Scriptures and the Fathers, we declare unanimously, in the proper noun of the Holy Trinity, that there shall be rejected and removed and cursed one of the Christian Church building every likeness which is made out of any cloth and color whatever by the evil art of painters.... If anyone ventures to represent the divine epitome (χαρακτήρ, kharaktír - grapheme) of the Word subsequently the Incarnation with material colours, he is an adversary of God. .... If anyone shall endeavour to correspond the forms of the Saints in lifeless pictures with material colours which are of no value (for this notion is vain and introduced by the devil), and does not rather represent their virtues as living images in himself, he is an adversary of God"[45]

- For iconoclasts, the merely real religious image must be an exact likeness of the paradigm -of the same substance- which they considered impossible, seeing forest and paint equally empty of spirit and life. Thus for iconoclasts the only truthful (and permitted) "icon" of Jesus was the Eucharist, the Body and Blood of Christ, according to Orthodox and Catholic doctrine.

- Whatever truthful prototype of Jesus must be able to stand for both his divine nature (which is impossible because it cannot exist seen nor encompassed) and his human nature (which is possible). But by making an icon of Jesus, one is separating his human and divine natures, since only the human tin can exist depicted (separating the natures was considered nestorianism), or else confusing the human and divine natures, because them 1 (wedlock of the human being and divine natures was considered monophysitism).

- Icon apply for religious purposes was viewed every bit an inappropriate innovation in the Church, and a render to pagan practise.

Information technology was besides seen as a departure from ancient church tradition, of which in that location was a written record opposing religious images. The Spanish Synod of Elvira (c. 305) had declared that "Pictures are not to be placed in churches, so that they exercise non get objects of worship and adoration",[47] and some decades afterward Eusebius of Caesaria may have written a alphabetic character to Constantia (Emperor Constantine's sis) saying "To depict purely the homo form of Christ before its transformation, on the other hand, is to suspension the commandment of God and to autumn into infidel error";[49] Bishop Epiphanius of Salamis wrote his letter 51 to John, Bishop of Jerusalem (c. 394) in which he recounted how he tore down an image in a church and admonished the other bishop that such images are "opposed … to our religion",[l] although the actuality of this letter of the alphabet has also long been disputed, and remains uncertain.[51] Still, as Christianity increasingly spread among gentiles with traditions of religious images, and especially later on the conversion of Constantine (c. 312), the legalization of Christianity, and, later on that century, the institution of Christianity as the state religion of the Roman Empire, many new people came into the new large public churches, which began to be decorated with images that certainly drew in part on regal and pagan imagery: "The representations of Christ as the Almighty Lord on his judgment throne owed something to pictures of Zeus. Portraits of the Mother of God were not wholly contained of a pagan past of venerated mother-goddesses. In the popular mind the saints had come to fill a part that had been played by heroes and deities."[52]"Satan misled men, so that they worshipped the brute instead of the Creator. The Law of Moses and the Prophets cooperated to remove this ruin...But the previously mentioned demiurge of evil...gradually brought back idolatry under the appearance of Christianity."[46]

Iconophile arguments [edit]

The master theological opponents of iconoclasm were the monks Mansur (John of Damascus), who, living in Muslim territory equally counselor to the Caliph of Damascus, was far enough away from the Byzantine emperor to evade retribution, and Theodore the Studite, abbot of the Stoudios monastery in Constantinople.

John declared that he did not worship matter, "but rather the creator of thing." He also alleged, "Merely I also venerate the matter through which conservancy came to me, equally if filled with divine energy and grace." He includes in this latter category the ink in which the gospels were written as well as the paint of images, the woods of the Cross, and the body and claret of Jesus. This distinction between worship and veneration is key in the arguments of the iconophiles.

The iconophile response to iconoclasm included:

- Assertion that the biblical commandment forbidding images of God had been superseded by the incarnation of Jesus, who, existence the second person of the Trinity, is God incarnate in visible matter. Therefore, they were not depicting the invisible God, but God as He appeared in the flesh. They were able to adduce the issue of the incarnation in their favour, whereas the iconoclasts had used the event of the incarnation confronting them. They also pointed to other Old Testament evidence: God instructed Moses to brand two aureate statues of cherubim on the lid of the Ark of the Covenant according to Exodus 25:eighteen–22, and God also told Moses to embroider the drape which separated the Holy of Holies in the Tabernacle tent with cherubim Exodus 26:31. Moses was likewise instructed past God to embroider the walls and roofs of the Tabernacle tent with figures of cherubim angels according to Exodus 26:ane.

- Further, in their view idols depicted persons without substance or reality while icons depicted real persons. Essentially the argument was that idols were idols because they represented simulated gods, not because they were images. Images of Christ, or of other real people who had lived in the past, could not be idols. This was considered comparable to the Quondam Testament practise of but offer burnt sacrifices to God, and non to whatever other gods.

- Regarding the written tradition opposing the making and veneration of images, they asserted that icons were part of unrecorded oral tradition (parádosis, sanctioned in Catholicism and Orthodoxy as administrative in doctrine by reference to Basil the Not bad, etc.), and pointed to patristic writings approving of icons, such as those of Asterius of Amasia, who was quoted twice in the tape of the Second Council of Nicaea. What would have been useful evidence from modern fine art history as to the apply of images in Early Christian art was unavailable to iconodules at the time.

- Much was fabricated of acheiropoieta, icons believed to be of divine origin, and miracles associated with icons. Both Christ and the Theotokos were believed in potent traditions to take sabbatum on unlike occasions for their portraits to exist painted.

- Iconophiles further argued that decisions such as whether icons ought to exist venerated were properly made past the church assembled in council, not imposed on the church by an emperor. Thus the statement also involved the outcome of the proper relationship between church and country. Related to this was the observation that information technology was foolish to deny to God the aforementioned honor that was freely given to the human emperor, since portraits of the emperor were common and the iconoclasts did non oppose them.

Emperors had ever intervened in ecclesiastical matters since the fourth dimension of Constantine I. As Cyril Mango writes, "The legacy of Nicaea, the first universal council of the Church, was to bind the emperor to something that was non his concern, namely the definition and imposition of orthodoxy, if need be by force." That practice continued from kickoff to stop of the Iconoclast controversy and across, with some emperors enforcing iconoclasm, and two empresses regent enforcing the re-institution of icon veneration.

In fine art [edit]

The iconoclastic period has drastically reduced the number of survivals of Byzantine fine art from before the menstruum, especially large religious mosaics, which are at present almost exclusively found in Italy and Saint Catherine's Monastery in Egypt. Of import works in Thessaloniki were lost in the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 and the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). A big mosaic of a church building council in the Purple Palace was replaced by lively secular scenes, and at that place was no issue with imagery per se. The apparently Iconoclastic cross that replaced a figurative prototype in the apse of St Irene's is itself an nigh unique survival, but careful inspection of some other buildings reveals like changes. In Nicaea, photographs of the Church of the Dormition, taken earlier it was destroyed in 1922, show that a pre-iconoclasm standing Theotokos was replaced by a large cross, which was itself replaced by the new Theotokos seen in the photographs.[53] The Prototype of Camuliana in Constantinople appears to have been destroyed, as mentions of information technology cease.[54]

Reaction in the West [edit]

The catamenia of Iconoclasm decisively ended the so-called Byzantine Papacy nether which, since the reign of Justinian I 2 centuries before, the popes in Rome had been initially nominated past, and afterwards but confirmed by, the emperor in Constantinople, and many of them had been Greek-speaking. Past the finish of the controversy the pope had canonical the cosmos of a new emperor in the W, and the old deference of the Western church to Constantinople had gone. Opposition to icons seems to have had little support in the West and Rome took a consistently iconodule position.

When the struggles flared up, Pope Gregory Ii had been pope since 715, not long later on accompanying his Syrian predecessor Pope Constantine to Constantinople, where they successfully resolved with Justinian Two the bug arising from the decisions of the Quinisext Council of 692, which no Western prelates had attended. Of the delegation of 13 Gregory was one of only two non-Eastern; it was to be the final visit of a pope to the city until 1969. At that place had already been conflicts with Leo Three over his very heavy taxation of areas nether Papal jurisdiction.[30]

See besides [edit]

-

Quotations related to Byzantine Iconoclasm at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Byzantine Iconoclasm at Wikiquote - Aniconism in Christianity

- Feast of Orthodoxy

- Libri Carolini

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b Humphreys, Mike (2021). "Introduction: Contexts, Controversies, and Developing Perspectives". In Humphreys, Mike (ed.). A Companion to Byzantine Iconoclasm. Brill'southward Companions to the Christian Tradition. Vol. 99. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. pp. i–106. doi:10.1163/9789004462007_002. ISBN978-90-04-46200-7. ISSN 1871-6377. LCCN 2021033871.

- ^ Halsall, Paul (2021) [1996]. "Medieval Sourcebook: Iconoclastic Council, 754 – Image OF THE DEFINITION OF THE ICONOCLASTIC CONCILIABULUM, HELD IN CONSTANTINOPLE, A.D. 754". Internet History Sourcebooks Project. New York: Fordham Academy Center for Medieval Studies at the Fordham University. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold Joseph (1987). A Study of History: Abridgement of volumes 7-10. p. 259. ISBN9780195050813.

- ^ a b Mango (2002).

- ^ Schildgen, Brenda Deen (2008). "Destruction: Iconoclasm and the Reformation in Northern Europe". Heritage or Heresy: 39–56. doi:10.1057/9780230613157_3. ISBN978-one-349-37162-4.

- ^ Herrin, Judith (2009-09-28). Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire. Princeton Academy Press. ISBN978-0-691-14369-ix.

- ^ Byzantine iconoclasm

- ^ Brubaker & Haldon (2011), p. 32.

- ^ Kitzinger (1977), pp. 101 quoted, 85–87, 95–115.

- ^ von Grunebaum, G. East. (Summertime 1962). "Byzantine Iconoclasm and the Influence of the Islamic Environment". History of Religions. ii (one): 1–x. doi:10.1086/462453. JSTOR 1062034. S2CID 224805830.

- ^ Wickham, Chris (2010). The Inheritance of Rome. England: Penguin. ISBN978-0140290141.

- ^ Kitzinger (1977), p. 105.

- ^ Cormack (1985), pp. 98–106.

- ^ a b Gero, Stephen (1974). "Notes On Byzantine Iconoclasm In The Eighth Century". Byzantion. 44 (1): 36. JSTOR 44170426.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1990). Byzantium The Early Centuries. London: Penguin. p. 354. ISBN0-fourteen-011447-five.

- ^ "Byzantine Icons". World History Encyclopedia. 30 October 2019.

- ^ Mango, Cyril A. (1986). The Fine art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents. University of Toronto Press. pp. 166. ISBN0802066275.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1990). Byzantium The Early Centuries. London: Penguin. p. 355. ISBN0-14-011447-five.

- ^ Brubaker & Haldon (2001).

- ^ Noble (2011), p. 69.

- ^ C. Mango and R. Scott, trs., The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor (Oxford, 1997).

- ^ C. Mango, ed. and tr., The brusk history of Nikephoros (Washington, 1990).

- ^ M.-F. Auzépy, tr., La vie d'Étienne le jeune par Étienne le Diacre (Aldershot, 1997).

- ^ I. Ševčenko, "Hagiography in the iconoclast period," in A. Bryer and J. Herrin, eds., Iconoclasm (Birmingham, 1977), 113–31.

- ^ A. Louth, tr., Three treatises on the divine images (Crestwood, 2003).

- ^ C.P. Roth, tr., On the holy icons (Crestwood, 1981).

- ^ M.-J. Mondzain, tr., Discours contre les iconoclastes (Paris, 1989), Exodus 20:ane-17.

- ^ Chocolate-brown, Chad Scott (2012). "Icons and the Beginning of the Isaurian Iconoclasm under Leo 3". Historia: The Alpha Rho Papers. ii: i–9. Retrieved 31 Oct 2019 – via epubs.utah.edu.

- ^ Mango (1977), p. i.

- ^ a b Beckwith (1979), p. 169.

- ^ Volcanism on Santorini / eruptive history at decadevolcano.net

- ^ Co-ordinate to accounts by Patriarch Nikephoros and the chronicler Theophanes

- ^ a b Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford University Press, 1997

- ^ The Oxford History of Byzantium: Iconoclasm, Patricia Karlin-Hayter, Oxford University Press, 2002.

- ^ Mango (1977), pp. 2–3.

- ^ David Knowles – Dimitri Obolensky, "The Christian Centuries: Volume 2, The Middle Ages", Darton, Longman & Todd, 1969, p. 108-109.

- ^ Haldon, John (2005). Byzantium A History. Gloucestershire: Tempus. p. 43. ISBN0-7524-3472-1.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks Project".

- ^ a b Cormack (1985).

- ^ Pratsch (1997), pp. 204–5.

- ^ Pratsch (1997), p. 210.

- ^ Scriptor Incertus 349,one–18, cited past Pratsch (1997, p. 208).

- ^ Pratsch (1997), pp. 211–12.

- ^ Pratsch (1997), pp. 216–17.

- ^ Hefele, Charles Joseph (February 2007). A History of the Councils of the Church building: From the Original Documents, to the close of the Second Council of Nicaea A.D. 787. ISBN9781556352478.

- ^ Epitome, Iconoclast Council at Hieria, 754

- ^ "Canons of the church council — Elvira (Granada) ca. 309 A.D." John P. Adams. January 28, 2010.

- ^ Gwynn (2007), pp. 227–245.

- ^ The letter'due south text is incomplete, and its authenticity and authorship uncertain.[48]

- ^ "Letter 51: Paragraph 9". New Appearance.

- ^ Gwynn (2007), p. 237.

- ^ Henry Chadwick, The Early Church building (The Penguin History of the Church building, 1993), 283.

- ^ Kitzinger (1977), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Beckwith (1979), p. 88.

References [edit]

- Beckwith, John (1979). Early Christian and Byzantine Fine art (2nd ed.). Penguin History of Fine art (now Yale). ISBN0140560335.

- Brubaker, Fifty.; Haldon, J. (2001). Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era, c. 680-850: the sources: an annotated survey. Birmingham Byzantine and Ottoman Studies. Vol. 7. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN978-0-754-60418-1.

- Brubaker, L.; Haldon, J. (2011). Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era, c. 680-850: A History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-43093-seven.

- Cormack, Robin (1985). Writing in Gold, Byzantine Society and its Icons. London: George Philip. ISBN054001085-5.

- Gwynn, David (2007). "From Iconoclasm to Arianism: The Construction of Christian Tradition in the Iconoclast Controversy". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. 47: 226–251.

- Kitzinger, Ernst (1977). Byzantine art in the making: main lines of stylistic development in Mediterranean fine art, 3rd-7th century. Faber & Faber. ISBN0571111548. (United states: Cambridge Academy Press)

- Mango, Cyril (1977). "Historical Introduction". In Bryer & Herrin (eds.). Iconoclasm. Eye for Byzantine Studies, University of Birmingham. ISBN0704402262.

- Mango, Cyril (2002). The Oxford History of Byzantium.

- Noble, Thomas F. 10. (2011). Images, Iconoclasm, and the Carolingians. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812202961, ISBN 9780812202960.

- Pratsch, T. (1997). Theodoros Studites (759–826): zwischen Dogma und Pragma. Frankfurt am Main.

Further reading [edit]

- Leslie Brubaker, Inventing Byzantine Iconoclasm, Bristol Classical Press, London 2012.

- A. Cameron, "The Language of Images: the Rise of Icons and Christian Representation" in D. Wood (ed) The Church and the Arts (Studies in Church History, 28) Oxford: Blackwell, 1992, pp. 1–42.

- H.C. Evans & W.D. Wixom (1997). The glory of Byzantium: art and culture of the Centre Byzantine era, A.D. 843-1261 . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9780810965072.

- Fordham University, Medieval Sourcebook: John of Damascus: In Defense of Icons.

- A. Karahan, "Byzantine Iconoclasm: Ideology and Quest for Power". In: Eds. K. Kolrud and G. Prusac, Iconoclasm from Antiquity to Modernity, Ashgate Publishing Ltd: Farnham Surrey, 2014, 75–94. ISBN 978-1-4094-7033-5.

- R. Schick, The Christian Communities of Palestine from Byzantine to Islamic Rule: A Historical and Archaeological Study (Studies in Tardily Antiquity and Early Islam two) Princeton, NJ: Darwin Press, 1995, pp. 180–219.

- P. Brown, "A Dark-Age Crisis: Aspects of the Iconoclastic Controversy," English Historical Review 88/346 (1973): 1–33.

- F. Ivanovic, Symbol and Icon: Dionysius the Areopagite and the Iconoclastic Crisis, Eugene: Pickwick, 2010.

- Due east. Kitzinger, "The Cult of Images in the Age of Iconoclasm," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 8 (1954): 83–150.

- Yuliyan Velikov, Prototype of the Invisible. Image Veneration and Iconoclasm in the Eighth Century. Veliko Turnovo University Press, Veliko Turnovo 2011. ISBN 978-954-524-779-8 (in Bulgarian).

- Thomas Bremer, "Verehrt wird Er in seinem Bilde..." Quellenbuch zur Geschichte der Ikonentheologie. SOPHIA - Quellen östlicher Theologie 37. Paulinus: Trier 2015, ISBN 978-3-7902-1461-1 (in German language).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_Iconoclasm

0 Response to "What Was the Iconoclastic Controversy and How Did It Affect Secular and Religious Art?"

Post a Comment