Hillary Clinton Stole My Nose Americas Funnisest

"I don't hate the Clintons," says R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr., the founder and longtime editor of The American Spectator and the father of … let's call it "Clinton disdain." "I have always seen them as comic figures." Tyrrell's particular brand of fun began when, in 1993, he sent a reporter to dig through the Clintons' tax returns and discovered that they had listed donations of Bill's old underwear as a tax write-off, valued at $1 each. But as the couple settled into the White House, the allegations grew darker. Later that year, Tyrrell and some cronies hatched the "Arkansas Project," a $2.4 million effort, financed by the right-wing philanthropist Richard Mellon Scaife, to delve deeper into the Clintons' past. Whitewater, Troopergate, and the death of Vince Foster were merely the highlights. Over the years, Tyrrell wrote dozens of columns and four books filled with murky Clintoniana. He accused the couple of abusing staff and benefiting from a cocaine-smuggling operation run out of an Arkansas airport. He claimed that Bill had bought women string bikinis in Rio and perfume in Sydney. Tyrrell's sources were often described merely as "sources" or "sources familiar with the questioning." But even Tyrrell had his limits. He grew indignant when he thought that Terry McAuliffe, a close friend of the Clintons and now the governor of Virginia, had accused him of calling the president a murderer. A complete falsehood! In fact, Tyrrell had merely quoted The Economist, which had noted a "peculiar pattern of suicides and violence" surrounding "people connected to the Clintons."

I caught up with Tyrrell recently in a cozy room in his Alexandria, Virginia, home that he refers to as the Lincoln library, owing to the large portrait of Abraham Lincoln hanging above the fireplace. Robert Todd Lincoln gave the painting to his great-great-grandfather Patrick D. Tyrrell for his role in uncovering a crime boss's plot to steal the president's corpse and hold it for ransom. At 71, Tyrrell has grown spare and birdlike, resembling an impeccably dressed minister who sometimes forgets to eat. But he still has a bit of 12-year-old boy left in him. Perched on a distressed-leather wingback chair, he took great delight in reading aloud the index of his 2007 book, The Clinton Crack-Up, which he swears he intended as a joke (sample: "Clinton, William Jefferson (Bill), Sex life of, Recreational sex, Zoo sex, Unspeakable sex"). Tyrrell began his career as a gifted and wide-ranging conservative polemicist, but over the years the Clintons came to take up most of the room in his psyche. His weirdest book, 1997's The Impeachment of William Jefferson Clinton, is an alternative history as it unfolded in Tyrrell's id, in which Clinton is undone by a series of newly discovered Nixon-style White House tapes. (Tyrrell leaves the specifics to the imagination.) But though The Spectator's circulation soared from 30,000 to more than 300,000 during the Clinton-scandal years, it fell to 75,000 in the early 2000s and has since plummeted to 16,000, according to Tyrrell. The magazine has also run into financial and legal trouble; you could make a good case that Tyrrell's Clinton obsession essentially killed it. The Spectator's most recent print issue appeared last summer, and Tyrrell doesn't anticipate another until this summer.

Unlike the nastiest Obama hatred—which is typically rooted in a fear of the Other (black, with an Arabic middle name, product of a mixed marriage)—Clinton disdain had a strange kind of intimacy. It was like hating a sibling who was more popular, more successful, more beloved by your parents—and always getting away with something. Tyrrell felt he knew the Clintons, because he'd gone to college with so many Clinton types: draft dodgers, pot smokers, '60s "brats." They were "the most self-congratulatory generation in the American republic," he tells me. "And it was all based on balderdash! They are weak! The weakest generation in American history!"

When Tyrrell writes about Hillary Clinton, he adopts a tone of hostility one might use for an ex-wife. He once ran into Bill and Hillary at a restaurant, for example, and as he recounts it, she "glared at me like a viper about to strike a rodent." The portrait Tyrrell paints of "the Lady Macbeth of Little Rock" is a little too personal. In his 2004 book, Madame Hillary: The Dark Road to the White House, he describes her when she first arrived in Arkansas as having "baggy" clothes and eyebrows so "thick," they "would have collected coal dust in a Welsh mining village." He claims that Hillary hurled "tirades and flying objects" at "Bill's defenseless skull," and that when they lived in the governor's mansion, the household cook declared, "The devil's in that woman."

Tyrrell is well aware that, in anticipation of Hillary's presumed 2016 candidacy, a new generation of journalists is trolling the archives in Little Rock and discovering new tidbits. Last year, for example, The Washington Free Beacon, a scoop-driven conservative online newspaper, uncovered an old journal that had belonged to Hillary Clinton's close friend Diane Blair, who died in 2000. In it, Blair recounted Hillary's having told her that for Bill, sex with the "narcissistic loony tune" Monica Lewinsky had no "real meaning," and that a psychologist had explained that the reason he cheated was because he had been torn between two mother figures as a child.

Tyrrell knows that these new, younger reporters and investigators understand the insatiable appetite for Clinton gossip, and have a sense of what makes a good story. He also recognizes that they have some skills he lacks, such as pushing an item out on social media to help it go viral. Theoretically, he should be able to slip into a comfortable retirement knowing that Clinton disdain has landed in fresh, capable hands. But he can't, because he also knows that this new generation sorely lacks "a sense of history," a true grasp of how the Clintons fit into the whole Baby Boomer nightmare of "sexual peccadilloes, lack of regard for the truth, and inability to heroically stand up for anything."

In the 1990s, Clinton disdain was like hating a sibling who was more popular, more successful, more beloved by your parents—and always getting away with something.

Up to this point in our conversation, Tyrrell had been polite and jovial, but now he moved out of lazy-Sunday-morning mode and to the edge of his chair.

"They wouldn't understand that the Clintons used Arkansas state troopers as pimps."

It was as if someone had propped him up before an audience, pushed a button, and turned him on. More pronouncements poured forth, at least half a dozen, a heated "lest we forget" filtered through the National Enquirer.

"They wouldn't understand that Clinton and Mrs. Clinton privately hired PIs to harass the women who were sleeping with him."

"They wouldn't understand the repeated thwarting of election laws and financial caps on fund-raising."

"They wouldn't understand the funny money coming out of China and other parts of Asia."

"They wouldn't understand that she stole White House furniture."

And so on.

When the 2016 presidential campaign was just a glimmer in the distance, at least a dozen conservative organizations had already dedicated themselves to Hillary Clinton's defeat. They are a combination of opposition-research shops, media outlets, and grass-roots activist groups. A couple have stationed staff in Little Rock to rifle through files in search of something new—or even something old that can be framed in a newly relevant way.

In the 1990s, Hillary Clinton famously complained about the "vast right-wing conspiracy" that was out to get her and Bill. But at the time it was really more a small, ragtag band of conspiracy-minded compatriots, albeit very noisy ones. Tyrrell's Spectator relied largely on a young investigative journalist named David Brock, who in 1997 would recant much of his reporting in an Esquire piece, "Confessions of a Right-Wing Hit Man," and a subsequent book, Blinded by the Right. (In one of the many odd twists since that era, Brock now runs a pro-Clinton super PAC.) Scaife, the Arkansas Project's backer, paid a handful of reporters, notable among them Christopher Ruddy, to write articles and books about the Clintons that the mainstream press mostly regarded with skepticism. Other scandalmongers depended largely on the Drudge Report to promote stories, hoping that the site would help them get picked up by legitimate news outlets. Fox News was then still a fledgling network, and the many conservative Web sites that are now familiar didn't exist. The movement was small, outside the Republican mainstream, and animated by a sense of "us against the world," recalls Brock, "which made the crusade seem more personal."

If she runs for president in 2016—as all evidence suggests she will—Hillary Clinton will face something more like a vast right-wing conglomerate. This time around, the groups will be well funded, solidly professional, and thoroughly integrated into the party establishment. America Rising, which employs more than 50 people, is a new opposition-research group that's preparing a Clinton strategy for the Republicans far in advance of the campaign. It sends "trackers" with portable video cameras to all her events, in hopes of catching a gaffe, and uses polling and focus-group research to determine ways to define her before she has a chance, once again, to define herself. The Free Beacon has its own research division and a "war room" for what it calls "combat journalism"—most of it, recently, directed at Clinton. The small but busy Stop Hillary PAC is putting together a "grass-roots coalition" that aims (as its name suggests) to ensure "Hillary Clinton never becomes president." Citizens United, the group that won the Supreme Court case allowing a flood of new campaign spending, is producing a movie about Clinton's performance as secretary of state, focusing on whether she did enough to protect the U.S. Embassy in Benghazi, where militants killed the U.S. ambassador to Libya and three other Americans in 2012. Americans for Prosperity, a group funded by the Koch brothers, turned its conference last August into a forum for a wide range of Hillary bashing.

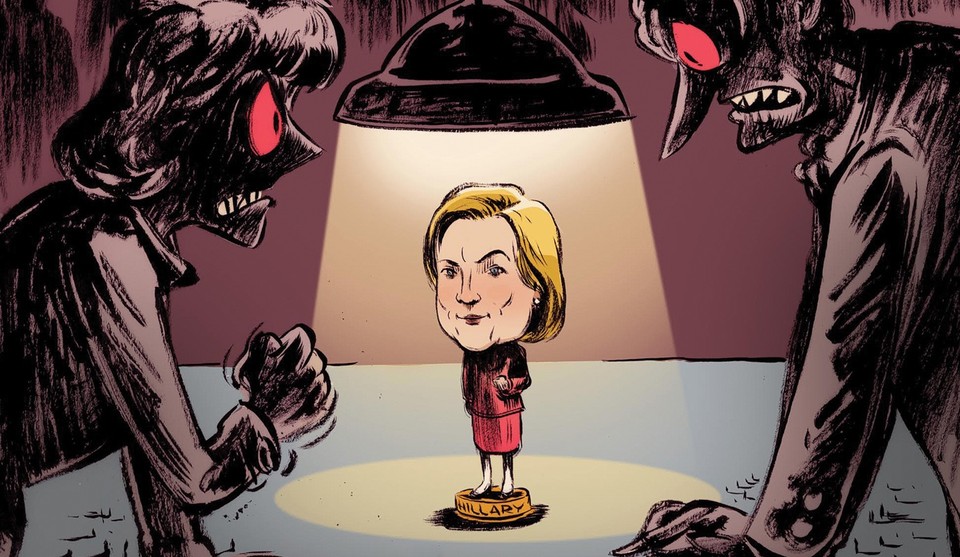

Collectively, these and other conservative outfits have the potential to substantially hurt Clinton's chances in the next election. Recall how the Swift Boat Veterans for Truth managed to reverse John Kerry's reputation as a war hero. He instead became defined by a picture of him windsurfing in Nantucket—a copy of which, not coincidentally, now hangs in the America Rising office. The success of these groups depends on many things—most obvious, the Republican nominee who winds up delivering their message. But another significant factor will be which brand of anti-Clinton warfare grabs the most attention: the over-the-top, Spectator -like paranoia that held sway in the 1990s or a sharper strategy that succeeds in tarnishing Clinton's reputation while still seeming to mainstream voters eminently reasonable and just.

Republicans don't need a deep sense of history to see that Clinton disdain is like an infectious disease: if it rages out of control, it can easily kill its host. Stories about lesbian encounters in a White House shower or crack pipes meant as ornaments for a White House Christmas tree (both from the former FBI agent Gary Aldrich's 1996 book, Unlimited Access) may sell, but they won't win an election. In addition to obscuring justified accusations of wrongdoing, such tawdry tales are likely to elicit sympathy for Hillary Clinton, especially in an age when trashing a prominent woman typically carries some cultural penalty. Also, the re-airing of any of the wilder Clinton conspiracy theories is likely to harm the messenger more than the target. Take Representative Dan Burton of Indiana: though he served 30 years in Congress, he will forever be known as "Watermelon Dan" for shooting a melon with a revolver in his backyard, as part of his attempt to prove that the Clintons' friend Vince Foster did not commit suicide but was instead murdered because he could implicate them in Whitewater.

Republicans particularly dread loose cannons at this political moment. In the 2012 elections, various off-the-cuff candidate musings (for instance, speculation about "legitimate rape" by Representative Todd Akin of Missouri) made the entire party look backwards and loony, and it paid a price in lost congressional seats. In 2014, the GOP was determined not to make the same mistakes—and for the most part, it didn't. The result was that Republicans gained control of both the House and the Senate, and now enjoy a more favorable national impression than they have in years. Wanting to hold on to that honeymoon mood, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell had one message for Republicans in the new Congress, summarized by The Washington Post in January: don't be "scary." Translated for 2016, the warning to his party is clear: keep the Clinton crazies muzzled.

In March 2013, The Washington Post ran a story about the launch of America Rising. The coverage was unusual: opposition-research shops don't normally seek out attention from major papers; they prefer to operate under the radar. (As a 2000 story in the New York Post put it, "Oppo research is like underwear—it works best when you don't see it.") But this new firm, founded by Mitt Romney's 2012 campaign manager, Matt Rhoades, planned on "instigating nothing less than a revolution in the way the right does and uses oppo research," according to The Washington Post. Tim Miller, the executive director of America Rising, told the paper, "Research has been people sitting in a dungeon or going through trash cans and then funneling the information up to a press person." Miller, by contrast, issues frequent press releases and sometimes even writes op-eds. He speaks like the CEO of a public corporation. "Part of our brand is having credibility with journalists," he told me.

Oppo shops used to be content with any nasty tidbit that got attention—for example, the infamous rumor leading up to the 2000 South Carolina presidential primary that John McCain had a black love child. But now, with constant political coverage from online media, random rumors have no staying power. The best dirt has become the kind that can help build a consistent and unappealing image of a candidate, or even an entire party. Oppo researchers today function in ways that make them almost indistinguishable from campaign strategists, just without the funding limits. They can provide one crucial piece of information—say, that John Edwards paid $400 for a haircut—that is subsequently integrated into the broader negative picture of a candidate (in Edwards's case, that he was rich and vain). Last year, a tracker from America Rising caught Bruce Braley, a Democratic Senate candidate in Iowa, deriding the state's senior senator, the Republican Chuck Grassley, as a "farmer from Iowa who never went to law school." This turned into a meme that made Democrats look anti-farmer and alienated from Middle America. For 2016, America Rising is building a huge database of everything Hillary Clinton has said and done, regarding everything from Little Rock to Benghazi, to try to paint a robust caricature of Hillary in the public's mind before the real Hillary even gets started.

When Clinton went on tour to promote her new book, Hard Choices, for instance, America Rising was determined to counter all the free positive press. It sent trackers to record her every move and updated its site constantly. It aggregated unflattering news coverage, but almost always from reputable origins—a Politico summary of negative reviews of her book; or a Wall Street Journal poll showing that only 38 percent of voters thought she was "honest and straightforward"; or a Daily Mail article reporting that "U.S. taxpayers spent $55,000 on travel expenses for Hillary Clinton's book tour," including "a $3,668-a-night hotel suite." The trick for America Rising is to find material that is damaging but still credible and mainstream. "If we were caught peddling really terrible stuff, wild conspiracy theories, it would have a terrible impact on our brand," Miller told me.

An already-emerging line of attack is the framing of Clinton as a plutocrat: elite, rich, and out of touch with average Americans. In some ways, it's the evolution of the old portrayal of the Clintons as vulgar money-grubbers, Arkansas grifters involved in an assortment of sleazy deals all the way down to trading old underwear for tax breaks. Now, by contrast, they are portrayed as operating on a much grander scale, acquiring their money from universities, charities, and shady international ventures. Whenever possible, America Rising cites the perks that go along with the Clintons' new wealth. Last September on the group's Web site, a story based on a Bloomberg News video appeared under a breathless headline: "$25,000 to Burn? Bill Clinton Smokes World's Most Expensive Cigar!" (In the video, the CEO of Gurkha—whose high-end cigars retail for $25,000 a box—mentions that Clinton is one of his clients.)

"If anything, the Hillary Clinton network now is the '90s influence-peddling Bill Clinton network on steroids," Miller told me. "It's had time to grow from a little operation in Arkansas. Now the circus is the global financial elite—CEOs and rich hedge-fund pals all looking to make deals, and the Clintons more than happy to participate. It's way more relevant for 2016!"

Among its efforts to gather information, America Rising has filed Freedom of Information Act requests to learn the details of the Clintons' speaking appearances at public universities. Such requests have already proved a fertile source of outrage stories in traditional media outlets. For example, The Washington Post reported in November that Hillary Clinton was paid $300,000 to give a half-hour speech at UCLA. (It also noted that her speaking agent requested that she be provided with a wedge of lemon in room-temperature water, a special rectangular pillow, and hummus and crudités in the green room.)

This line of attack could be especially potent against what has emerged as one of Clinton's regular talking points, the vanishing American dream of upward mobility. When she brings up the plight of a single mother struggling to work and take care of her children, America Rising can point out just how long it takes a middle-class family to earn the $300,000 that she pocketed for one speech. And you can be sure that there will be many, many reminders of Hillary's comment last summer that she and Bill were "dead broke" when they left the White House.

That said, if clumsily executed, the Hillary-as-plutocrat offense could easily summon a different set of stereotypes about how unseemly money and power look on a woman. The stories on America Rising's Web site may stick to the facts, but much of the accompanying art is in the realm of tabloid cheap shot. When photos of Clinton appear on the group's home page, she is almost always wearing one of a few unflattering expressions: chin up haughtily, angry and finger-pointing, bored and contemptuous, or laughing with her mouth wide open. In one photo, accompanying the aggregated story about billing taxpayers for her book tour, she seems to be rubbing her hands together as she leaves the stage.

Teaching Republicans how to not turn off women voters is one of the goals of Burning Glass Consulting, a group founded by Katie Packer Gage and two other female GOP campaign veterans and based just outside Washington, D.C. "Women have this feeling that the world—and particularly this town—is run by men, and if something comes across as mean or unfair, they want to rush to [Clinton's] defense," Gage says. "We have to make sure nothing comes across as 'unfair.' " To this end, Burning Glass conducts focus groups with women in informal settings, with wine or cappuccino, to explore their feelings about Clinton. It tests potential strategies to see which ones might be persuasive, and then checks in with the women periodically, to see whether the impact was enduring or temporary. Most voters in presidential elections are women, and most women vote Democratic. But the majority of white women have voted Republican in the past four presidential elections. The most obvious battle in 2016 will be for married white women, who have been drifting Republican but may, by virtue of shared life experiences, lean toward Clinton.

One criticism of Clinton that Burning Glass has found to resonate with women is an attack Obama used successfully against her in 2008: that she is "more politically motivated" than the average politician. In general, people tend to view women as political outsiders. They assume that their motives are more pure than those of their male counterparts, and that they are in it not just for themselves but for some greater good. In its focus groups, however, Burning Glass has found strategies that, over time, can take this asset away from Clinton, and convince women that she is more political than the average candidate. One is to suggest inappropriate overlap between her work at the State Department and at the Clinton Foundation. The firm points out that one of Secretary Clinton's aides was also consulting at the foundation, which might have created a conflict of interest. The aim is not to uncover a scandal, but rather to show that Clinton operates just like the boys: she works the system and stacks it with cronies, making them all rich in the process. It's an approach that Burning Glass has found can make respondents "significantly less likely to support" Clinton in 2016.

Between "plutocrat" and "too political," a useful caricature of Clinton emerges. She's not the hardworking secretary of state, dutiful, experienced, and breaking glass ceilings. She's a jet-setter, hobnobbing all over the world, making herself and her friends rich, and using her career as a public servant to build her personal brand.

That's the restrained scenario. But a host of other anti-Clinton groups and individuals operate by the anything-goes rules of the 1990s. In 2008, Citizens United brought us Hillary: The Movie, in which Kathleen Willey, one of Bill's alleged mistresses, claimed that the Clintons contracted someone to murder her cat. The group's upcoming Benghazi movie is likely to be comparably over the top. The New Hampshire–based Hillary Project, meanwhile, describes itself as dedicated to "waging war on Hillary's image." So far, this has primarily involved putting lewd captions on unflattering pictures of Clinton ("Learned Foreign Affairs From Bill: Won't Pull Out Until Finished").

Garrett Marquis is a senior adviser at the Stop Hillary PAC. He is only 31 years old, but he can reel off the 1990s scandals as fluidly as R. Emmett Tyrrell can. His goal, he says, is to introduce Millennials to "the reality of who she is, not who she says she is." (The group's treasurer, Dan Backer, is blunter still: "Hillary the brand is bull——," he told The Washington Post.) An ad the group shot last year, using the kind of ominous voice-over and grainy footage that the History Channel reserves for major war criminals, offers a stroll down memory lane: Whitewater, Vince Foster, Travelgate, the Rose Law Firm, Benghazi. (The Rose Law Firm—gives you shivers, right?) With the exception of Benghazi, it's hard to envision any of these gaining much traction with the voting public. They didn't, after all, back when Bill Clinton was president, and now they have the added problem of being ancient history—especially for Millennials. "Conservatives will recycle old scandals, and it will hurt them, just like it did in the '90s," says Christopher Ruddy, who is rueful about the excesses of his reporting at the time. "People like me constantly firing at her made a lot of other people rally to her support."

"Women cut other women a lot of slack when it comes to infidelity," says one GOP operative. "We just have to be careful we're not doing anything that makes [Clinton] a sympathetic character."

But even the Stop Hillary PAC ad declines to mention the more memorable scandals, involving Bill's infidelity: Gennifer Flowers, Paula Jones, and Monica Lewinsky. Conversations on this topic prompted the most agony in the researchers I spoke with. On the one hand, revisiting those old sex scandals—and perhaps even uncovering new ones—could be rich territory in an era with much less tolerance for sexual harassment. Jones and Lewinsky, for instance, would look more like straightforward victims now; lumping them together as "bimbo eruptions" (in the Clinton aide Betsey Wright's infamous phrasing) would be highly offensive.

On the other hand, Bill is not the one running for office, and many in the GOP think talk about his sex life could backfire. "Women cut other women a lot of slack when it comes to infidelity," says Katie Gage. "We just have to be careful we're not doing anything that makes [Clinton] a sympathetic character." Some women could see her as a victim, and others—including the married white women whom Republicans want to hold on to—could identify with her as a fellow scarred warrior on the battlefield of marriage. Some might admire her for keeping her marriage intact for so long, and ultimately winding up as the spouse in a position of power.

Figuring out which of the Clinton scandals still feel relevant and which don't is a work in progress, and The Washington Free Beacon functions as a kind of laboratory for throwing things at the wall and seeing what sticks. The online paper's editor, Matthew Continetti, is also in his early 30s, but he has that young-old-man look in the way of conservatives: sport coat, shellacked hair, everything but the bow tie. We met for lunch at the Bombay Club, where he dines often and the waiters know what he likes. Continetti started out at The Weekly Standard and became the son-in-law of its founder, William Kristol. But he split off on his own because while he was interested in Republican trench warfare, he was also interested in pop culture and GIFs and memes and generally operating with a faster metabolism.

The Free Beacon has experimented with pretty much every form of Clinton attack: she's an old radical; she makes excuses for her cheating husband; she lied about Benghazi; her book sales tanked. In September, the site published a newly discovered 1971 letter from an adoring young Hillary Clinton to the left-wing organizer Saul Alinsky. "Dear Saul," she began. "When is that new book [Rules for Radicals] coming out—or has it come and I somehow missed the fulfillment of Revelation?" The story was accompanied by a familiar photo of college-age Hillary with her Gloria Steinem hair. Continetti says he published the correspondence "because it's something we haven't seen before." But so far, it hasn't gotten much traction. Hillary the radical college leftist mostly just creates cognitive dissonance with who she is now, a distinguished elder, an ex-senator and ex–secretary of state with a sometimes hawkish bent who has banked $5 million in speaking fees and a rumored $14 million advance for Hard Choices.

The Free Beacon is perhaps most true to its Millennial self when it drops the Little Rock excavation and just pokes fun at Clinton. As Continetti explains, "I see her as a high-school teacher I really dislike, who can do you harm but you can still snigger about behind her back." The clearest image that emerges from The Free Beacon's coverage is of Clinton not as a radical leftist or an injured wife or even a jet-setting member of the global elite, but rather as just a boring old politician. Continetti recalled listening to Bill Clinton's speech at the 2012 Democratic Convention and, despite himself, nodding along. "I couldn't help myself!" But Hillary "lacks that hypnotic quality," he told me. When Hard Choices came out, The Free Beacon took the rare step of quoting a liberal CNN commentator, Sally Kohn, because she said the memoir looked like "a yawner." In a 2014 column, Continetti wrote that Clinton "represents the past," which is among the gentlest ways the paper has referred to her age. Other articles have proclaimed: "Affluent Grandmother Is 2016 Frontrunner," "Memory Problems Could Doom Hillary's White House Run," and "Grandmother Hillary Clinton, 67, is vying to become one of the oldest world leaders in history." When People magazine put her on its cover, The Free Beacon's editors gleefully dived into the debate about whether she was leaning on a walker in the photo. (Her hands were, in fact, on a patio chair.)

But while this age-based approach may work for an online newspaper that delights in tabloid antics, whether a GOP presidential candidate can adopt it is another question altogether. The 2016 Republican field has the obvious advantage of including several faces who are younger and newer to politics. Marco Rubio, the 43-year-old senator from Florida and a possible contender, did recently try out a more dignified version of the age critique, calling Clinton "a 20th-century candidate" who "does not offer an agenda for moving America forward in the 21st century." Katie Gage, from Burning Glass, advises staying far away from direct questions about Clinton's age. She told me that even Republican-leaning women her firm talks with immediately cite some version of "Ronald Reagan was old, and he ran for president." The idea that women have an expiration date and men don't is especially sensitive. At the same time, Gage says there are tactful ways to suggest that Clinton is out of touch: "You can talk about the age of her ideas," as Rubio did. It's also fair to point out that she hasn't generated much excitement or buzz, "that young women don't necessarily feel even the connection with her that they felt with Barack Obama." And, Gage adds, "when [Clinton] talks about how she and her husband sit around and watch Antiques Roadshow, well, it's just not seen as that cool."

There may be no one who better understands just what a delicate balancing act Clinton disdain can entail than Barbara Comstock. In the 1990s, as a 30-something Republican congressional staffer, Comstock made a name for herself as one of the most dogged investigators of that era's Clinton scandals. She was known for holding all-night vigils in her office to keep Democrats from breaking in and stealing crucial legal documents. Last year, when Comstock made her first bid for Congress, in suburban Virginia, Politico set the stage for an epic showdown: "Fifteen years later," the site announced, "the Clinton Wars are back."

Early on, Comstock looked as though she were preparing for a fight. When asked about Benghazi in a radio interview shortly after her primary, she immediately spoke about her work in the 1990s, "where we were just blocked at every turn." Yet following the Politico story, Comstock never again spoke in public about Benghazi, and laughed off any mention of her work in the 1990s as old news.

This perhaps should not come as too great a surprise, given that in the intervening years, Comstock played a central role in the professionalization of opposition research—essentially ensuring that something like the Clinton wars would never again unfold in quite the same histrionic, gossip-laden way. In 2000, when Comstock was hired by David Israelite to take over the research shop at the Republican National Committee, she replaced most of the existing staff with lawyers and policy experts. "We wanted to develop a research operation that was fact-based and very responsible, so there would be no question about sourcing methods or where a piece of information had come from," Israelite told me. Comstock wrote papers using open sources and footnotes. But just as important, she used what she found to "connect the dots and create a coherent story about an opposing candidate," Israelite recalled. For example, Comstock's team developed the story that Al Gore had been leasing some of his property in Tennessee to a zinc mine that had several times violated Environmental Protection Agency guidelines, adding to an impression of the environmentalist as pious and hypocritical. The new, methodical Barbara Comstock had rendered the old, obsessive model obsolete.

If Republicans are lucky, Comstock's story will serve as proof that the early, paranoid years of Clinton disdain drew upon a very particular generational context, a civil war between the Boomers. The straightlaced types looked at the Clintons and saw everything they hated about the hippie 1960s and early 1970s: draft dodging, feminist excess (Hillary Rodham wasn't "baking cookies"), Saul Alinsky–style radicalism, casual drug use, and sexual promiscuity. Every time something came up that conservatives thought should be disqualifying—past pot use and the ridiculous "I didn't inhale" defense; Bill's infidelities with Gennifer Flowers, then Paula Jones, then Monica Lewinsky—somehow the Clintons got away with it (which is just a less flattering way of calling someone a "comeback kid," the label that was attached to Bill for rebounding from exactly these episodes).

One of the more interesting elements of the cultural response to the 1990s Clintons was the feeling Hillary evoked in conservative women. In his book, Brock writes that Comstock told him she couldn't get Hillary's "sins off her brain 'because Hillary reminds me of me. I am Hillary.' " Comstock has never confirmed anything in Brock's book, and she declined to be interviewed for this article. But her comment lines up with what other women of that era have expressed. In her 2000 polemic, The Case Against Hillary Clinton, the former Republican speechwriter Peggy Noonan wrote of herself:

I look at Mrs. Clinton and see the kneesocked girl in the madras headband [meaning Noonan herself], the Key Club president who used to walk into the bathroom in Rutherford High School, wrinkle her nose at the tenth-grade losers leaning against the gray tile walls, leave, go down the hall, and mention to a teacher that they're smoking in the girls' room again. That's my own private Hillary, or at least one aspect of her.

Comstock was also part of a generation of conservative women who were living a difficult contradiction. She worked for a Republican establishment that had a narrow view of family values, yet she was known for pulling all-nighters during Travelgate, when she had three young kids at home.

"One way to interpret that would be, they were projecting their own internal angst onto Hillary," Brock says. "They didn't necessarily hate Hillary. They hated something about themselves, and they were projecting that onto the kind of woman Hillary represented." But that contradiction has since melted away. Now, The Washington Post reported, Comstock keeps her phone in a case that says Women Rule and is an "evangelist for Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In." The crucial turning point in her congressional campaign came when her opponent, John Foust, mused about whether Comstock had ever had a "real job." Comstock took feminist umbrage, and won over the district's many working women in part by declaring his remark "sexist" and "intentionally demeaning."

That's the problem with critiques of the Clintons that are deeply rooted in specific cultural tensions. Over time, many of those tensions subside, even if the issues remain unresolved. Indeed, one of the most striking aspects of Clinton disdain is the degree to which so many of its most vehement early adherents have moved on. At one end of the spectrum is David Brock, who went from Clinton tormentor to Clinton loyalist. At the other end, perhaps, is Barbara Comstock, who has decided that there's no political advantage in refighting old battles. In between are people like Richard Mellon Scaife, the principal funder of the "vast right-wing conspiracy," and Christopher Ruddy, who was, after Brock, perhaps its most high-profile messenger. (Ruddy's 1997 book, The Strange Death of Vincent Foster: An Investigation, not only implicated the Clintons in Foster's death but went so far as to accuse Kenneth Starr of being privy to the cover-up and a "patsy for the Clintonites.") After Scaife met Hillary Clinton face-to-face in 2008, when she visited the editorial board of his paper, the Pittsburgh Tribune-Review, he wrote a column saying he had come away with a "very favorable" impression of her. When Scaife died last year, no less than Bill Clinton himself gave a eulogy at the memorial service, saying that for all their differences, Scaife "fought as hard as he could for what he believed in." Ruddy, too, has made peace with his onetime targets, even arranging a lunch with his friend Scaife and Bill Clinton in 2007. Now the CEO of the conservative Web site Newsmax, Ruddy has decided that he went too far back in the day. "There was just so much ferment back then, and we got carried away," he told me. "People get emotional. It was almost like a war, but a political one." Today Ruddy, who says he is most likely to support the GOP candidate in 2016, will even allow that Clinton "will be a good president. She's going to surprise a lot of people."

And then, of course, there's R. Emmett Tyrrell Jr. In his foyer, Tyrrell keeps all the personal presidential mementos he's been given over the years. There's a picture of him meeting with Ronald Reagan. Then one of Richard Nixon jumping on a trampoline. And then, more oddly, a photo of Bill Clinton with his arm around Tyrrell. There's nothing to indicate that it is different from the other photos, that those are admiring and this one mocking. Tyrrell says the picture was taken when he got a friend to invite him as her date to Bill Clinton's 60th birthday party. And while he presents it as a prank, it's clear that he genuinely wanted to attend. Indeed, he seemed the tiniest bit annoyed while recounting that when he got to the front of the photo line, Clinton gave no sign of recognizing him.

Tyrrell said he saw Clinton once more at the end of the party, when both of them walked into the bathroom at the same moment. Two old guys, facing off once again in the realm of underwear. By now, it's clear which man won. Tyrrell's magazine is a footnote, in danger of going under once and for all. Bill Clinton, on the other hand, may be on the verge of returning to the White House with his wife. But that doesn't mean Tyrrell is giving up. Before our interview was over, he offered me one final scoop. "Bill," he reported, "didn't wash his hands."

Source: https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/03/among-the-hillary-haters/384976/

0 Response to "Hillary Clinton Stole My Nose Americas Funnisest"

Post a Comment